One of the ironies about the current state of academe is that universities propose to introduce students to what is called “critical thinking” as if most teaching faculty are available and capable to do this very work. I remember a biology professor wagging his finger in my face because, he said, biology students really don’t need to know how to write. That he was a well regarded professor made the moment doubly remarkable. “Don’t you want your students to be successful grant writers?” I asked. “You don’t need to take writing courses to do that!” he sniffed. Opposition to writing and the teaching of same is fundamentally a resistance to the teaching of nuance, scruple, irony, and pesky associative questions like “why is this problem interesting; confounding; worthwhile; perhaps even utopian?” Whatever we mean by the term critical thinking behind the term must lie a hope that students will bloom beyond being students. If this isn’t your hope as a member of the professoriate—which is to say a wish that your students will master their own curiosities no matter their chosen profession, then you’ve no business teaching. And there. I’ve said it. I believe far too many faculty are insufficiently inclined to engage with students as potential contrarians which is what we all should be after.

How many department meetings have I attended over the years? Lordy. And scarcely a discussion about students or what we hope they’ll gain. Worse perhaps is the cynical shorthand of “outcomes assessment” that’s been adopted for inclusion on syllabi and which now occupies senior administrators from the accreditation complex—themselves former faculty who’ve little experience teaching critical thinking. In this way the contemporary academy is like the singsong monkey that chases its tail around the flagpole. There’s a lot of talk about critical thinking and little actually happening. Instead there is essentialism about any number of topics. Here’s a popular one: Capitalism is the source of all suffering. I think one should say it’s the source of many problems. But critical thinking demands probing the assertion: was there ever a civilization without some kind of capitalism? Are there capitalist countries where the people are happy? These questions are not popular in essentialist teaching circles. Essentialism requires agreement, a prescriptive shared narrative. I know disabled students who think all able bodied citizens are their enemies and that able bodied people believe in compulsory able-bodiedness.

Remember “The Combahee River Collective Statement” of 1977?

“This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.”

As Mark Lilla puts it in his book “Once and Future Liberal” the left, following Reagan’s election failed to unite and instead augured into separate coverts of bitterness:

“Instead, they lost themselves in the thickets of identity politics and developed a resentful, disuniting rhetoric of difference to match it. ”

**

Three weeks ago I watched the televised memorial for President George H.W. Bush. I found the occasion moving. Bush 41 signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law in 1990 and that moment still stands for me and many others as a watershed in American politics as it was perhaps the last time the left and right worked assiduously to promote the well being of millions upon millions of citizens. The law was fiercely opposed then and still is now. That Bush signed it says a good deal about his willingness to resist calls from the Chamber of Commerce to let the disabled continue living without rights as they’d always done.

When I posted on social media my appreciation for Bush’s role in promoting the ADA I was besieged by Facebookers and Twitterers informing me Bush was a moral coward, a bigot, a war criminal, a homophobe, a liar, a groper—all to edify me. Having said he’d done something good I must be obtuse or utterly ignorant about his life in its entirety. This is the sloppiness of identity politics—its execrable cheapness of thought, adopted formally at the Combahee conference and now a laziness disguised as moral advantage. If critical thinking is to be taught let’s ask what it might actually mean.

I’ll venture it may require a willingness to give up first response finger wagging—the “gotcha” which is now everywhere on both the right and left. Someone who teaches disability studies told me on Facebook (in response to my observation that much about racism I find hard to absorb having grown up in a very liberal environment) I “must be” racist as I’m white. Her proof? I’m soaked in white privilege. Gotcha works this way. It substitutes paradigms within an argument. Example: “You believe you’ve a personal identity which is moral and possesses Enlightenment values of nuance and rationality but actually you’ve no personal identity since postmodern culture assures this. Therefore you can’t be immune to racism, if say, you’ve gotten a bank loan at any time during your life.”

If you’ve white privilege you’re a de facto racist. The essentialism behind the argument—the confirmation bias—is that this has been entirely decided by people who recognize oppression better than I do.

Forget that I grew up blind; have lived on food stamps and unemployment and have spent time living in Section 8 housing. Dispose of the fact I’ve been discriminated against in education and employment over and over during my “career”—that fancy term for what the Buddhists call the “meat wheel.”

That I’ve been harmed owing to disability doesn’t change the fact that I have advantages over others. If you believe this than you also have to imagine that human beings are just flies in amber, mere products of ancient entrapments with no hope of escape.

**

Why is this “gotcha” so attractive?

Fundamentalism is easier than scruple.

Amos Oz died this week. I’ve been reading his book “Dear Zealots” with considerable interest. He is at pains to understand how fanaticism works and why it’s the illness of our time. He writes:

“Fanaticism is not reserved for al-Qaeda and ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra, Hamas and Hezbollah, neo-Nazis and anti-Semites, white supremacists and Islamophobes and the Ku Klux Klan, Israel’s “hilltop thugs” in the settlements, and others who would shed blood in the name of their faith. These fanatics are familiar to us all. We see them every day on our television screens, shouting, waving angry fists at the camera, hoarsely yelling slogans into the microphone. They are the visible fanatics. A few years ago, my daughter Galia Oz directed a documentary film that probed the roots of fanaticism and its manifestations in the Jewish underground.

But there are far less prominent and less visible forms of fanaticism around us, and perhaps inside us, too. Even in the daily lives of normative societies and people we know well, there are sometimes revelations, albeit not necessarily violent ones, of fanaticism. One might encounter, for example, fanatic opponents of smoking who act as if anyone who dares light a cigarette near them should be burned alive. Or fanatic vegetarians and vegans who sometimes sound ready to devour people who eat meat. A few of my friends in the peace movement denounce me furiously, simply because I hold a different view of the best way to achieve peace between Israel and Palestine.

Certainly, not everyone who raises a voice for or against something is suspected of fanaticism, and not everyone who angrily protests an injustice becomes a fanatic by virtue of that protest and anger. Not every person with strong opinions is guilty of fanatic tendencies. Not even when such views or emotions are expressed very loudly. It is not the volume of your voice that defines you as a fanatic, but rather, primarily, your tolerance—or lack thereof—for your opponents’ voices.

Indeed, a hidden—or not so hidden—kernel of fanaticism often lies beneath various disclosures of uncompromising dogmatism, of imperviousness and even hostility toward positions you deem unacceptable. Righteousness entrenched and buttressed within itself, righteousness with no windows or doors, is probably the hallmark of this disease, as are positions that arise from the turbid wellsprings of loathing and contempt, which erase all other emotions there is nothing wrong with loathing in and of itself: in Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky and Brecht, Chaim Nachman Bialik and Y. H. Brenner and Hanoch Levin, we find a stinging component of loathing. A blazing component—but not an exclusive one. In the works of these great writers, loathing is accompanied by other feelings, too—by understanding, compassion, longing, humor, and a measure of sympathy.)”

**

If the American university hopes to embrace critical thinking it must examine righteousness entrenched. In literary writing courses we talk of comic or dramatic irony—those moments when a literary writer asks “what do my characters or my narrator know “now” that they did not know even just a few moments ago? In a dramatic stage play comic irony is when the audience knows more than the figures on stage. All of Shakespeare’s comedies depend on this device.

If the American university hopes to embrace critical thinking it must offer courses that show students how to work across divides. My suggestion is to look at the history of the Americans with Disabilities Act—it has a long back story, driven by veterans wounded in foreign wars, pushed by political activism—cripples crawling up the Capitol’s steps; grassroots politics of the best and worst kind; and perhaps most remarkable of all its demonstration that intellectual and dogmatic buttresses can come down just as architectural barriers can.

If the American university wants to embrace critical thinking it should look at the peacemakers.

Amos Oz again:

“There are varying degrees of evil in the world. The distinction between levels of evil is perhaps the primary moral responsibility incumbent upon each of us. Every child knows that cruelty is bad and contemptible, while its opposite, compassion, is commendable. That is an easy and simple moral distinction. The more essential and far more difficult distinction is the one between different shades of gray, between degrees of evil. Aggressive environmental activists, for example, or the furious opponents of globalization, may sometimes emerge as violent fanatics. But the evil they cause is immeasurably smaller than that caused by a fanatic who commits a large-scale terrorist attack. Nor are the crimes of the terrorist fanatic comparable to those of fanatics who commit ethnic cleansing or genocide.

Those who are unwilling or unable to rank evil may thereby become the servants of evil. Those who make no distinction between such disparate phenomena as apartheid, colonialism, ISIS, Zionism, political incorrectness, the gas chambers, sexism, the 1 percent’s wealth, and air pollution serve evil with their very refusal to grade it.

Fanatics tend to live in a black-and-white world, with a simplistic view of good against evil. The fanatic is in fact a person who can only count to one. Yet at the same time, and without any contradiction, the fanatic almost always basks in some sort of bittersweet sentimentalism, composed of a mixture of fury and self-pity.”

“The urge to follow the crowd and the passion to belong to the majority are fertile ground for fanatics, as are the various cults of personality, idolization of religious and political leaders, and the adulation of entertainment and sports celebrities.

Of course there is a great distance between blindly worshiping bloodthirsty tyrants, being swept up by murderous ideologies or aggressive, hateful chauvinism, and the inane adoration of celebrities. Still, there is perhaps a common thread: the worshiper yields his own selfhood. He longs to merge—to the point of self-deprecation—with the throng of other admirers and unite with the experiences and accomplishments of the object of worship. In both cases, the elated admirer is subjugated by a sophisticated system of propaganda and brainwashing, a system that intentionally addresses the childish element in people’s souls, the element that so longs to merge, to crawl back into a warm womb, to once again be a tiny cell inside a huge body, a strong and protective body—the nation, the church, the movement, the party, the team fans, the groupies—to belong, to squeeze in with a crowd under the broad wings of a great father, an admired hero, a dreamy beauty, a sparkling celebrity, in whose hands the worshipers deposit their hopes and dreams, and even their right to think and judge and take positions.

The increasing infantilization of masses of people everywhere in the world is no coincidence: there are those who stand to gain from it and those who ride its coattails, whether from a thirst for power or a thirst for wealth. Advertisers and those who fund them desperately want us to go back to being spoiled little children, because spoiled little children are the easiest consumers to seduce.”

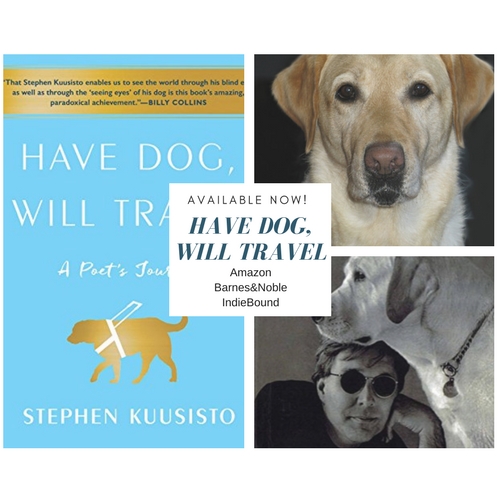

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger